This blog was originally published on October 23, 2012 on the New Existentialist Blog. It was republished here after the New Existentialist Blog was discontinued.

It is easy to become disgusted with politics in the United States today. Corruption seems to be the norm, and there does not appear to be any genuine hope for change. We blame the politicians, the politician system, the parties, and the media, but rarely do we consider our role—the role of the general public. In this blog, I am going to argue that we need to take a closer look at the role of the general public and the voters, and advocate for an empathetic interpretation of our political candidates. This is not intended to say that the politicians and media do not bear a great amount of responsibility; in a previous blog, I even stated that politicians ought not be considered role models for our children because of much of their behavior. Rather, I am advocating that we ought not blame them without considering our role.

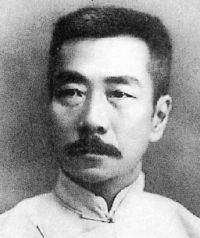

Zhi Mian

Zhi mian, as noted in the previous blog I referred to, is a concept recently introduced to the existential psychology literature through Xuefu Wang. According to Wang (2011), zhi mian is not easily translated into English, but a literal translation would be “to face directly.” Essentially, it refers to facing oneself, facing others, and facing life honestly and directly. Furthermore, it unifies these different ways of facing directly, suggesting that the only way to face oneself directly is to also face life and others directly.

Clearly, zhi mian is something lacking in politics, which is more about spin and rhetoric than truth, responsibility, and authenticity. Yet, if we are going to zhi mian politics, it must involve looking honestly at various aspects of the political process, including the role of the general public and voters. In other words, zhi mian advocates for collective responsibility when considering the political problems in the United States.

The Expectation of Lying

The idea for this article has been building for several years, but the more recent inspiration came when reading an internet news article noting results from recent poll that indicated people felt Romney was more dishonest than Obama, but that they expected both candidates to lie. This is a sad state of affairs, but I could not help but wonder: Is this all the fault of the politicians? Could a truly honest politician, who spoke the truth, really be elected to a high office today? Isn’t there an expectation to lie, to tell us what we really want to hear?

Most people know politicians lie; yet, we still endorse this behavior. We know they cannot fulfill all their campaign promises; yet, we praise them on the campaign trail then attack them later for not living up to these unrealistic promises. Although some politicians are shady characters from the outset, many begin as honest individuals wanting to positively impact the world. Once introduced to the political system, they soon learn many painful realities, such as that they are expected to lie, spin the truth, and be vicious in their attacks of the other candidate if they want to win. If you are an honest, caring person when beginning as a politician, this is a difficult position.

Critical Thinking & Flip Flopping

In science and philosophy, keeping an open mind to be swayed by the data is an asset; in politics, it is a liability. The best politicians should change their mind fairly frequently, but they should do it for the right reasons. Politicians are routinely expected to vote and make decisions on areas outside of their expertise. As they review the data, and continue to learn about the various issues on which they need to vote, they should become better informed and able to make more educated decisions. Yet, we expect politicians to make good decisions with little knowledge and then stick to that position despite what the evidence says.

When politicians make mistakes today, they often are expected to defend the mistake instead of apologizing and correcting the mistake. They are rewarded more for sticking to a bad decision than they are from learning. In essence, this is a system that says we do not want our politicians to learn!

I am not defending all instances when politicians change their positions. As is evident, often politicians change their position, or at least their stated position, for the wrong reasons. They conform to what the big donors expect, to align with the polls, or to agree with what their party pressures them to say. This is not authentic learning or change and should be discouraged. Yet, this change, done for the wrong reasons, is better tolerated than changing because one has become more informed and thought through the issues more thoroughly.

Think Skinned Politicians & Empathy

I have great empathy for how painful it must be for the politicians and their families as they have to sit through day after day of character attacks, including many that come from deceptive political spin and outright lies. My father, who was a state legislator, experienced some of this in his campaigns at the state level. It was very painful for my mother and him to go through this, but I am proud that he did so without resorting to such tactics in return. He was lucky that at the state level at the time he was running—you could still get elected as an honest politician with integrity. I suspect that would be more difficult now.

I have also experienced situations in my own life where I was being regularly criticized with spun half-truths and outright lies. Much like with politics, I knew that responding to these would have little effect. Some people would believe me, and some would believe the person who was criticizing me. This was extremely painful, but in the end, I had to accept that all I could do was try to live with integrity and trust that my character would be seen and trusted by most people.

What I experienced, and even what my father experienced, was nothing in comparison to what politicians at the national level, and sometimes even the state and local level, experience today. To be able to withstand such consistent and extreme attacks, one must develop a thick skin and learn to not react to these attacks. Yet, I have to wonder, at what cost? When one develops a thick skin, it is easy to develop a thick skin in areas where it is better to be thin-skinned, where empathy and compassion is what is needed. This leads me to wonder, have we created a political system that makes it difficult to remain compassionate and empathetic? If so, it is no wonder that there is so little concern for many of the people truly suffering. Their stories are great for the rhetoric of political speeches, but not powerful enough to penetrate the thick skins of the politicians using them.

What Can We Do?

So how is this our fault? We participate in this system when we condone these behaviors. When we, as a society, tolerate the news media sensationalizing these problems and turning them into entertainment, we support this behavior. We complain about the news media, yet continue to watch Fox News and MSNBC, and shows that dramatize these problems. We do not confront politicians when they misbehave. We allow attack adds to work. We buy into spin. I am sure many would respond defending themselves saying they are good at criticizing the spin, the deceptions, and the dramatizations—and this is likely true when it is done by the politician and political party that is not our own.

If we want things to change, we need accountability and accountability always starts at home. As Lu Xun (1919/1961) stated, “you have to reform yourself before reforming society and the world” (p. 52). First, we need to acknowledge our personal role. Second, we need to work to hold our own party and the politicians we support to be accountable. We can have no authenticity or credibility criticizing others if we do not authentically look at how we are contributing to the problem and work to change that.

Conclusion

Politics in the United States is a mess, no doubt. I must acknowledge that it is much easier for me to find the fault in the candidate I do not support, and easier to justify the behaviors of my candidate. Sadly, I have to wonder, if my candidate ran his campaign with perfect honesty and integrity and I knew that his approach would likely cost him the election, would I prefer that he lie and deceive or be honest? In reality, this scenario may be the case. That terrifies me.

References

Lu Xun (1961). Random thoughts. In Y. Xianyi & G. Yang (Eds. & Trans.) Lu Xun selected works

(Vol. 2). Beijing, China: Foreign Language Press. (Original work published in 1919)

Wang, X. (2011). Zhi mian and existential psychology. The Humanistic Psychologist, 39, 20246.

~ Louis Hoffman, PhD

Note: Although this site is owned by Louis Hoffman, it supports the Rocky Mountain Humanistic Counseling and Psychological Association (RMHCPA), which is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization. As an Amazon Associate, RMHCPA earns from qualifying purchases made through the links on this page.

When clients present with the desire to find oneself, I will say that I do believe gaining a better understanding of oneself is important and something for which I can offer help. I also will typically add that I believe that there are aspects of oneself that can be changed or are under the influence of the individual. It is not necessary that the client and I agree about the nature or definition of the self or engage in a philosophical discussion about this; however, I think it is important that we be honest in our conversations relevant to this topic, especially if it is connected to their reason for entering therapy. At times, if beliefs are held rigidly enough, it may signify that we are not a good fit to work together. However, I find most of the time that there are ways we can work together while honoring these differences.

When clients present with the desire to find oneself, I will say that I do believe gaining a better understanding of oneself is important and something for which I can offer help. I also will typically add that I believe that there are aspects of oneself that can be changed or are under the influence of the individual. It is not necessary that the client and I agree about the nature or definition of the self or engage in a philosophical discussion about this; however, I think it is important that we be honest in our conversations relevant to this topic, especially if it is connected to their reason for entering therapy. At times, if beliefs are held rigidly enough, it may signify that we are not a good fit to work together. However, I find most of the time that there are ways we can work together while honoring these differences.